Who Needs Educational Games When Entertainment Will Change the World?

Educational games have always carried a certain stigma. Nine times out of ten, if you ask any gamer if they prefer a game developed for educational purposes to a similar title made for the commercial market, the latter will win. He might look down his nose at you for good measure, too.

In his talk at the 2013 Games for Change Festival in New York City this week, serious games developer and academic Ian Bogost lifted the veil on the unspoken truth about ‘serious’ games: that many seem to be conceived as talking points for government foundations and non-profits, fodder for conference presentations, or low-hanging fruit for securing research grants. In other words, purposes outside of actually educating people through games.

But there was a greater truth that permeated several of the sessions over the course of the week: That, despite the decades-old preconception, entertainment is not the archetypal enemy of education. That, if anything, entertainment is paramount if you want to meaningfully teach anything through games.

“Education sometimes has this preconception that in order to educate, you have to do it in a dry, boring context. But learning should be a fun thing. Who says you have to suffer in order to learn?” –Nick Fortugno, Playmatics

Say you’ve landed a grant or contract to develop an educational or ‘serious’ game. What’s the first thing you do? It isn’t to identify the high-level goal, or nail down your target audience, or put a team together, or any of the basic pre-production tasks. It’s to resign yourself to the idea that the game will have to be boring, and mentally steel yourself to find ways to ‘unboringify’ the design enough to pass muster with the client.

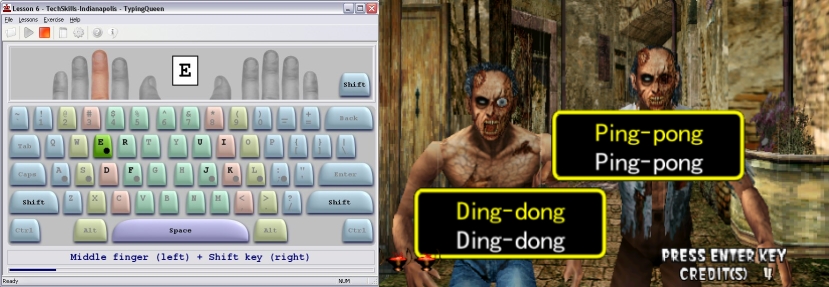

Perhaps inherited as part of the traditional educational model, there’s been a longstanding idea that you can have fun or you can learn, but you can’t do both at the same time. The milquetoast ‘edutainment’ label only furthers the failing of this idea by attempting to naïvely marry components from each ‘separate’ camp into an abomination where (hypothetically) everybody wins.

But do kids really want to play Ultra Rad Martian Fraction Adventures? No, they’d rather play anything else. Do teachers really want kids to play Hammond the Turtle’s Noble Gas Quest a week before the test? No, it’d be quicker to simply teach the periodic table the old-fashioned way.

“The problem [with edutainment] is with the way that creators of today’s edutainment products tend to think about learning and education. Too often, they view education as a bitter medicine that needs the sugar-coating of entertainment to become palatable. They provide entertainment as a reward if you are willing to suffer through a little education.” –Mitchel Resnick, MIT Media Laboratory

This bias against the concepts of play and fun as legitimate learning vehicles was in more literal view during another session at the conference. At Filament Games CEO Dan White’s talk on their award-winning game Reach for the Sun, he pointed out one specific problem teachers kept citing when asked if they would use the game in the classroom: that in order to play, students had to navigate to www.filamentgames.com. Just having the word “games” in the URL was enough to dissuade them from using the game.

It’s stranger still when you realize how other media forms deftly handle content meant to inform or educate, as opposed to purely entertain. Film and television documentaries have long dealt with serious and emotionally delicate topics while still presenting themselves as engaging, entertaining experiences.

Historical fiction is predicated on the concept of using an entertaining, made-up premise to communicate the facts and historical truths that hide within the lives of history’s lesser-known players. Even books on business can be entertaining, as Eli Goldratt’s The Goal heralded the advent of the business novel, slyly introducing new management paradigms alongside a story engaging in its own right.

“My focus is not to educate. My focus is to entertain… my goal is to entertain and passively educate.”

–Navid Khonsari, iNKstories

Far from capitulating to an ADD-riddled generation of dolts, entertainment is the glue of the human experience. If you are presented with something that doesn’t hold your attention – a book, a movie, a game, a picture, whatever – you aren’t intrinsically motivated to absorb all it has to offer you.

To reap the benefits of any experience in life, your sense of curiosity, of “what happens next?” needs to be activated. There’s a reason that “diversion” is synonymous with something entertaining: your attention has been captured, diverted from what you were doing before to being invested, engaged, and receptive to what is now being communicated to you. What better way to trigger this receptive mode than by entertaining?

Entertainment’s Power to Inspire

Creating engagement and instilling a sense of receptiveness isn’t the only benefit of entertainment. It can also inspire us all to think larger about what is not yet possible, and how we can help turn dreams into realities.

Last week saw another conference held in New York, but of a different stripe. The Global Future 2045 International Congress in Lincoln Center brought together futurists, scientists, roboticists and religious leaders to discuss what the next forefront of humanity would look like. Talks had grandiose titles like “Brain Control of Prosthetic Devices: The Road Ahead” and “The Goal of Technology is the End of Death.”

Yet among all the far-flung notions of the presentations, a pattern began to emerge. Dr. Theodore Berger’s presentation on engineering artificial memories seemed straight out of the 2004 film The Final Cut and the recently-released Remember Me. Nigel Ackland’s presentation of his bebionic arm, powered by seamlessly reading the minute movements of his forearm muscles, looked like something straight out of Terminator 2.

But this was no longer science fiction. Dr. Berger had successfully engineered artificially memories in lab rats. Nigel Ackland’s robotic arm was very much a working model, having lost his arm in a smelting accident.

All of the concepts, no matter how outlandish, had established roots in science fiction. Some had come to fruition, and some had not. But all this time it had been the writers, filmmakers and artists who had been preparing the next generation for the bounty of the future, inspiring youth to take these impossible dreams and work towards bringing them into the world.

And it won’t be Hammond the Turtle who lights a fire under the kid who grows up to bring the next great vision of the future to reality.

We’ll have entertainment to thank for that.