Can Games Rhyme?

Music, when soft voices die,

Vibrates in the memory;

Odours, when sweet violets sicken,

Live within the sense they quicken.Rose leaves, when the rose is dead,

Are heap’d for the belovèd’s bed;

And so thy thoughts, when thou art gone,

Love itself shall slumber on.

– Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Music, When Soft Voices Die”

Sticky Fingaz, from out your darkest fears

I make you meet your maker, make you meet the man upstairs

– Onyx, “React”

A rhyme is a curious thing. Cheesy in lesser hands, a well-formed rhyme has the odd property of elevating whatever the original sentiment is being expressed by sheer virtue of having the sounds be similar. Poets and songwriters have used this tool since time immemorial, elevating their works to be something else – to become, in the best cases, sublime experiences.

In the search for more meaningful, transformative gameplay experiences, is there a way to apply this principle to games? Is there a way to make games “rhyme”?

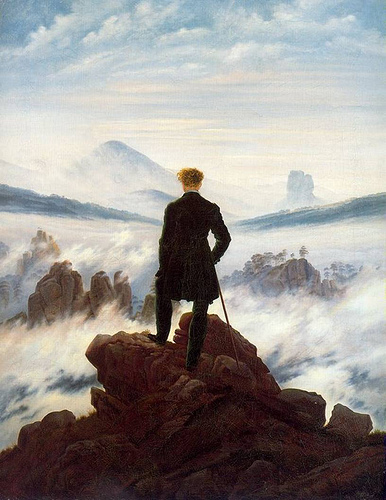

Rhyme to Find the Sublime

At its core, literal rhyming is simple: by unifying the language used and thought being expressed with sounds that mirror each other, you imply a deeper connection than what would otherwise come across in unmatched sounds. So where rhyming poetry is concerned, the power comes from the combination of language and sound.

While rhymes in this sense may seem like the sole domain of poetry, this attainment of a transformative, sublime feeling can be felt in superb examples of almost any other media, though unfortunately there isn’t a universal term for it. For the sake of this article, I’ll simply refer to the concept as “rhyming.”

In modern prose, particularly fiction of any length, literal rhyming would seem out of place and peculiar. Yet plenty of authors still accomplish the same degree of sublime meaning by unifying their characters’ actions with innately human truths. In other words, the works of fiction that we remember align action and subtext – what characters do, and the hidden reasons for why they do them – empowering the story with additional meaning.

In modern music, the effect can be reached by marrying the melody and language (lyrics) so that they combine in ways that accentuate the ideas being expressed by the words as well as the emotions being communicated by the music.

While there are many strains of “rhyming” in the performing arts, all of them – including theater, television and film – share core concepts that build toward bringing about this sense of cohesiveness.

The marriage of the performance and content – the body language, vocal tone and emotional expression of the actors, combined with the content they are communicating – is what brings about powerful reactions in audiences.

With bad actors, even Shakespeare is dreadful. With skilled performers, reviews will be better, but critics will still note that the actors are clearly better than the material.

Can Games Do It?

Which brings us to games. Anecdotally, most of us have experienced this sense of the sublime while playing one of our favorite games. But on an analytical level, what was actually happening? If we diagram exactly how games can transcend being an activity and become something more, will we be able to increase our understanding of how to get there?

Here are some possible ways to achieve “rhyming” in games.

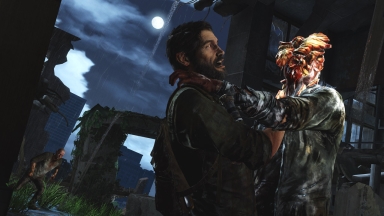

→ Activity & Theme. Marrying the activity (gameplay) that the player undertakes with the theme of the game is one a lot of developers talk about and aspire to, but most fail to understand how to truly achieve it.

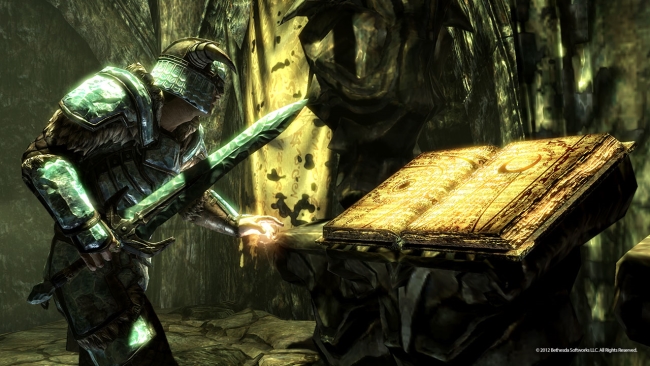

At first blush, you might think this only applies to narrative-focused games like The Last of Us, which uses this technique well – the player is mowing down waves of enemies to survive, just as the player’s character is fighting for his survival.

Yet this can also apply to games that don’t overly focus on the narrative, like Michael Brough’s 868-HACK. In that game, you carefully maneuver your avatar through a deadly computerized world of enemy AIs to fight and resources to steal in a quest to outwit the very rules of the game, much as a hacker would.

→ Activity & Aesthetics. Combining the activities the player undertakes with the visual and aural presentation of the game is another valid way to accomplish this. Rez used this concept as a foundation before development began, and Harmonix’s upcoming Fantasia seeks to explore a similar concept.

Having the player as an active participant in the creation of a game’s visuals or audio is a relatively direct way to establish this connection. The gargantuan success of the Guitar Hero and Rock Band series is clear proof.

→ Activity & Subtext. Different from activity and theme, subtext in this case alludes to the gameplay ramifications of making a particular choice, and is brought about when tight systems designed is a focus.

Fighting games are a perfect example of this. One of the reasons there is such a following for fighting game tournaments is that, once you’re familiar with a particular game’s set of characters, it becomes easier to understand each player’s motivations (both overt and hidden) by how they play their character. A missed opportunity to attack here might indicate sloppiness, or it might hide a grander strategy for later.

Much as how you can size up a chess opponent’s skill level by playing the game itself, making each available action have due consequence opens up the use of subtext to create greater meaning.

→ Activity & Mind. This last method refers to the concept of flow, popularized by Jenova Chen’s game of the same name. By carefully throttling gameplay sections between challenging and comfortable extremes, the idea is that you can bring about an engaging sense of “flow” where the player is consistently challenged just enough without being frustrated.

Once the player enters this state, the boundary between their physical self and the game all but disappears – until they shake their head and look up at the clock to discover three hours have gone by.

Plan Ahead

Can games reach the sublime? Yes – but in order to have the best chance of attaining it, first you must identify just how your game will get there.

While it’s certainly possible to combine any of the four approaches mentioned above, and surely there are additional ways that didn’t make the list, having a plan will allow you to best focus on delivering a memorable, meaningful game that players won’t soon forget.