Battling the Backlog: Curing No-Time-to-Play-Games-Itis

Few things in the game world garner as much simultaneous love and disdain as Steam’s annual summer sale. On the plus side, wildly discounted prices mean any game that has remotely been on your radar is suddenly attainable. On the downside, it’s easy to go on a spree while barely spending any money, piling up even more games on your To Play backlog.

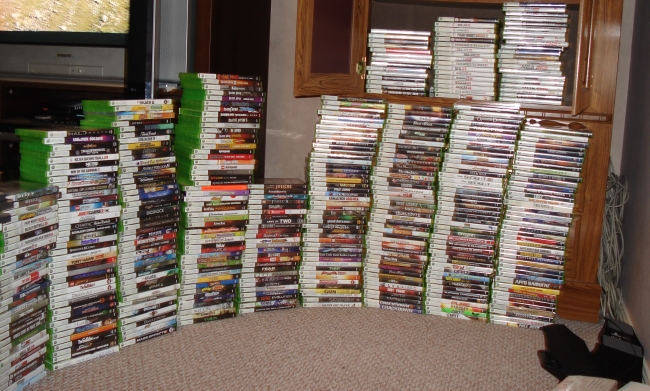

But beyond the memes and lighthearted first-world moping, there is a more serious issue worth investigating. The hate/love dynamic of the Steam sales comes from the fact that more and more gamers have accumulated stacks of unplayed games. Due to several factors – the rise of the indie community, cheaper and more effective development tools, a greater number of open platforms than in the past – more games are being released now than ever before, and many of them are worth playing.

From here, another confluence of events complicates things. For working developers, it’s an ironic fate. You become so busy making games that you find yourself with less and less time to actually play them. As gamers age into parenthood, more demanding jobs and other unavoidable obligations and life events, available time to play gets squeezed and squeezed.

Many game professionals insist that developers play games to stay informed of what the medium is producing, and the benefits of knowing what is being done, what is successful, and what is to be avoided can be invaluable in the development process. Yet we’re fallible as humans, and it’s easy to fall into a long stretch without playing anything. At this point you may gaze longingly at your ever-rising backlog of games, less out of desire to tear into the newest release and more of a sense of conquering the digital Everest of your own making.

Many game professionals insist that developers play games to stay informed of what the medium is producing, and the benefits of knowing what is being done, what is successful, and what is to be avoided can be invaluable in the development process. Yet we’re fallible as humans, and it’s easy to fall into a long stretch without playing anything. At this point you may gaze longingly at your ever-rising backlog of games, less out of desire to tear into the newest release and more of a sense of conquering the digital Everest of your own making.

This is the most dangerous part. At a certain point, one’s backlog becomes so intimidating it’s hard to look at without feeling a sense of obligation, and harder still to prevent the feeling from souring you on the prospect of cracking into it. Slowly but surely, the stack grows even higher as a monument to your inability to play.

The Symptoms

Note: What follows is an analysis of an extremely niche first-world problem. When all else fails, remember that games are luxury goods not critical to you or your loved ones’ survival.

The first step in a finding a cure is to identify the ramifications of not treating the problem. Here are some of the common side effects of an ossified game backlog.

Guilt. If you work in the industry, it’s easy to accrue ‘guilt points’ the longer you go without making progress in your backlog. A sense that you’re not doing your due diligence, that you’re letting down colleagues and your employer can creep into your everyday life if gone unchecked for too long, leading to higher stress and possibly depression.

On a personal level, it’s also easy to feel like you’re neglecting your favorite hobby, even if your time is spent doing valuable activities to manage other parts of your life.

Cultural poverty. Most of us have played a widely-discussed game just so we could finally talk about it. Not having time to play the most popular releases can leave you genuinely left behind on some trends. This is especially true for more ephemeral experiences like MMOs and other multiplayer-focused titles.

Didn’t have a Dreamcast in 2000? Whoops, then you’ll never get to experience Phantasy Star Online. Missed out on Tabula Rasa, 1 vs. 100 or Halo 2’s online multiplayer for Xbox? You’re out of luck because those games are gone forever.

While nobody can play everything, missing out on these types of fleeting game experiences can leave you with a paucity of reference materials when connecting trends, tracking the evolution of game mechanics or drawing inspiration for future projects. A fear of this sense of ignorance can build stress as well, mounting more pressure on you to finally attack the backlog (regardless if you do it or not).

While nobody can play everything, missing out on these types of fleeting game experiences can leave you with a paucity of reference materials when connecting trends, tracking the evolution of game mechanics or drawing inspiration for future projects. A fear of this sense of ignorance can build stress as well, mounting more pressure on you to finally attack the backlog (regardless if you do it or not).

Ignorance. Missing out on newer, more provocative titles can lock you out of reading some of the more insightful critical essays that are popping up online at a fast clip. While your personal tastes may differ from popular opinion, being able to participate in critical analysis of thought-provoking games like Starseed Pilgrim and Spec Ops: The Line can be hugely beneficial in giving you more game design fodder to consider when thinking theoretically and practically about your current projects.

The same goes for game conferences. Having a first-person understanding of what a game offers is all but mandatory for sitting in on GDC or IndieCade sessions that dive into a particular game at length.

And of course, there’s the memes. Woe to the fellow years late to the Portal party when nobody wants to hear about the goddamn cake anymore.

A Treatable Illness

So how do you tackle this affliction? The solutions are simple in theory, but harder in execution.

Set Deadlines/Check-in. I got my start in games as a reviewer years ago, but for a while after I would still write reviews for friends’ sites for fun, as long as they had deadlines. The practice of instituting deadlines alone is fantastic for providing motivation to finish a game, and the added bonus of having to summarize your experience in a review ensures that your playthrough is attentive and thoughtful.

Other deadlines can work, as long as the motivation is consistent. If you blog about games, you can easily work the requirement to play a new game or two into your routine. For Dashjump, I take an inventory of every game-related activity I’ve done since the previous week to make sure I have new experiences to draw from for new posts.

Game clubs are another under-utilized technique. Finding a group like the Double Fine Game Club can provide the external motivation and support to play regularly, and some libraries have even begun game programs in the spirit of book clubs. Can’t find a game club? Round up some friends, start a Facebook group and make your own.

Prioritize. It’s simple, really – if you aren’t playing as many games as you’d like, it’s because other things are taking priority in your life. A great place to start is by looking at what you actually spend your time on, and using this to draw a more accurate map of your priorities, tasks and responsibilities.

Stuck with double shifts for the next week and a half? Pencil in some play time once your schedule goes back to normal. Find yourself going to the same bar after work every day, even though you’d rather be at home or somewhere else? The first step in breaking unwanted habits is to identify them.

Once you’ve ascertained your priorities and figured out how gaming can fit in again, block out time during your week to play and treat it like an important business meeting. If you work in games, this isn’t that far from the truth!

Approach it out of love, not obligation. This one is critical. Even as you’re setting deadlines, re-prioritizing your life and scheduling dedicated game time, it is crucial that you maintain a spirit of love and enthusiasm for playing games. Avoid treating game time like an ‘appointment’ obligation similar to going to the dentist or getting your car inspected. Making room and setting aside time for playing games should be a fun thing you look forward to.

Should you feel that your time would be better spent doing other things, or that you’re wasting time parking yourself in front of a screen, just remember that games are a valid cultural medium and that they can add a richness to your life that complements all of the other things you do.

Being transported by a good book, being moved on an emotional level by a film – these experiences are close cousins of the well-played game.

And, when you’re ready, they will be there for you to discover again once you make the time.