Beyond the Straight White Dude: Why a More Diverse Game Industry Benefits All

The recent rise in promoting games developed by minorities, the LGBT community and women have brought a welcome critical eye to one of the more pervasive realities of game development: that game developers are, and for the most part have always been, straight white dudes. The groundswell of vocal advocates pushing for recognition for marginalized communities has been a refreshing conversation amid the usual industry stories of layoffs, indie successes and the long transition from console to mobile.

But there’s another huge reason to embrace the new generation of more diverse game makers, and it has nothing to do with practicing compassion or empathy. The simple truth is, the more diverse our game developers are, and the more viewpoints they draw from, the more varied, novel and new our gameplay experiences will be.

Let’s take a step back. When you take an in-depth look at the specific inspirations for some of your favorite games, you might be surprised at what you find. Will Wright was inspired by architecture and urban design for The Sims; the Legacy of Kain series’ titular character was inspired by Clint Eastwood’s character in Unforgiven; and yes, Super Meatboy was inspired by the brutally difficult platforming games of the late 80s.

The Sims went on to become an unlikely blockbuster hit, launching a new franchise and spawning clones. The Legacy of Kain series became a cult favorite for its dubious morality and compelling characters. Super Meatboy sold a boatload and is lauded as a testament to an unyielding indie vision to quality.

Yet which of these games tried something truly new? The one inspired by other games? Or the ones inspired by other fields and mediums?

“The last piece of advice on that level is fill the tanks, fill the tanks, fill the tanks. Constantly watch things and things you don’t [normally watch]. Step outside your viewing zone, your reading zone. It’s all fodder but if you only take from one thing then it’ll show.” –Joss Whedon

Another widely known but understated fact is that the dominant bulk of people who go on to work in games are those exposed to them as kids. Chris Suellentrop of The New York Times embodies this trend in a piece describing how he became enamored with games at an early age. The reason? In 1980, he received an Atari 2600 for Christmas.

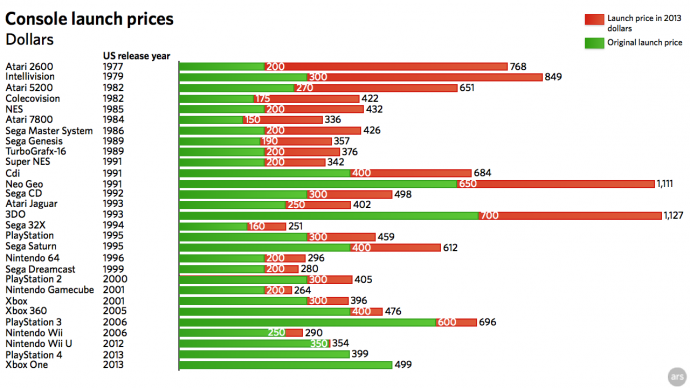

The interesting part about this story is that at launch, the Atari 2600 cost $200 – or roughly $768 in 2013 dollars. Yet while some of us weren’t as lucky as kids, there was always that one friend who had the latest system that we’d make sure to become buddies with. But again, this is a biased view of reality.

If only the kids whose parents were well-off enough to spend $700 on curiosities for their children were able to have the formative, inspirational experience that Suellentrop had, then we are most certainly cutting off a healthy chunk of the impoverished population from ever falling in love with games.

Granted, access to games is cheaper and more prevalent today than it has ever been. But today’s young would-be developers face a new obstacle: an industry entrenched with structures and beliefs instituted by the 80s trailblazer generation of developers. With such an emphasis on “cultural fit” in the average hiring process, it’s not unrealistic to imagine candidates more diverse than the typical straight white dude running into more barriers than they would otherwise face.

So what can we do about it? Plenty.

Looking into the past, we can identify several traits common to people who eventually became developers: They were inspired by games as kids, they had access to technology and tools, and they were either tenacious enough to fight for their dreams or capable (or lucky) enough to find help.

This is where we can make the biggest difference. Mentoring the next generation is one of the most direct ways to help usher in more diverse perspectives into games. For women, Pixelles in Montreal, Dames Making Games in Toronto and Women Who Code in San Francisco provide mentors and an educational context to help women developers improve their craft. Anna Anthropy’s call to action slash book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters served as a clarion call for the LGBT dev community.

Even things like posting on the TIGSource forums, helping someone out in a Facebook game dev group or hosting a game workshop for kids can help give someone with a burgeoning interest in games a proper introduction to what’s possible.

It all comes down to simple math – the more people exposed to games and game development, the greater the odds are that one of them goes on to create something unbelievable that would otherwise not have existed.

Better yet – if you do your part to help when they’re just starting out, they might have you to thank for it.