The Problem with Game Reviews (And Why Games Are Like Restaurants)

What’s the one thing missing from every book review that’s ever been written? The number at the end. Isn’t it interesting how books, an artistic medium thousands of years old, has resisted the kind of numerical classification that has invaded film, food, games, and even prospective romantic partners within the last century?

While the widely used star system may have been popularized in the late 1920s to offer a quick way to summarize lengthy film reviews, its ubiquity in film has long since been adopted by professional game reviewers, most often in the form of numerical scores. Yet the more you look at the usage of these grading systems for the unique medium of interactive games, the stranger the fit appears.

Start with film. Since films are linear and take approximately the same amount of time to complete, the criteria seems reasonable, with the question coming down to “Is this film that is roughly 90-120 minutes as good as this other film, which is also roughly 90-120 minutes?” Books arguably escape this rationale due to the wide range in pages and time needed to finish reading, especially since people read at different speeds. Now you have a variable in how the media is consumed that isn’t present for film, which complicates the simple comparison afforded by film reviews. Variables like this complicate assigning a subjective score based on a uniform experience.

It gets more confusing when you look at food reviews, specifically restaurants. Now, instead of looking purely at the experience of eating, you’re rating the entire experience of all of the things you could possibly eat, as well as the restaurant’s ambience, furnishings, layout, cleanliness, friendliness of the waitstaff, skill of the kitchen staff that night, etc.

Restaurant reviews still often boil down to a blunt number or star ranking, but the shift from the direct linear experience of film and books to the ‘big picture’ composition of the atmosphere and the food quality is a significant difference.

Then you have games.

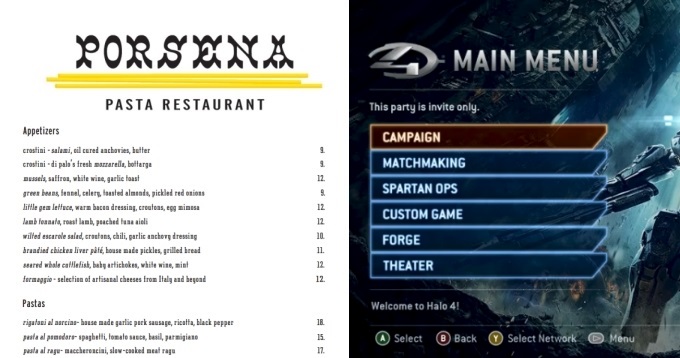

When you are first seated at a restaurant, what do you see? When you first start up a game, what do you see? That’s right, the menu. Far from linguistic serendipity, this is the first indication that games have more in common with restaurants than they do with traditional linear media.

In a restaurant, you study the menu in preparation for your few key choices – the meal decisions that will drive your experience. In a game, the menu screen is a launchpad for whatever type of experience you’re looking for at the moment (depending on the game, of course) – single-player story, multiplayer, challenge mode, coop, etc.

While this choice is much less permanent in games, both require the same initial input used to begin. It goes deeper – once you’re in the game, every action you take is essentially another, smaller, menu choice of all of the in-game options available to you. With every decision, a unique experience unfolds that reflects the aggregate choices of the designers and the mindset of the player at that given moment in time.

In the case of Halo 4, as you decide to rush, snipe, or grenade your foes, the game will ‘order up’ the experience you’ve decided on (melee battle/long-range shootout/evasive maneuvers) and serve you the corresponding simulation. Because you make so many of these choices as you sculpt your particular experience, their significance is diluted on average, leading to a sustained sense of control and lengthened immersion.

Compare this to a restaurant, where your choices are few, but have dramatic effects on your enjoyment. Better yet, look at buffets, where even more agency is given over to the participant to guide the experience (sandbox games) in exchange for giving up the authored experience of a professionally prepared meal (story-based linear games).

Looking at these linear and interactive mediums, the difference can be summed up easily:

In film, literature, and linear recorded media, you will have the same experience every time.

In games, dining, and interactive experiences where the participant has agency, while it’s possible to have the same experience every time, not only are the odds against it but the nature of the media discourages it.

And that’s where the legacy review systems show their limitations. If games are experiences that so depend on agency for their end results, relying on a reviewer to quantify their particular experience in a hard number is bound to be problematic. Remind me, what exactly is the difference between a game that gets a 6.8 and one that earns a 7.2?

Instead, looking at the reviewer’s particular experience as an indicator of all possible experiences that could be had with the game leads to a much more reasonable method. Building off of experiments to find a better way to phrase this, like defunct magazine Game Buyer’s Rent or Buy rankings, Kotaku’s rating system has come the closest to putting this into practice with a simple “Should you play it? Yes/No” question, with follow-up reasons to support the verdict.

Is it a perfect system? Probably not. Yet in the face of the complexity afforded by interactive experiences, sometimes the simpler ways are the best.